Gender equality is one of the pressing priorities to be addressed in education and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) call for ending discrimination against women, the elimination of violence and harassment especially against women, and universal access to reproductive health and rights. Nepal is a country rich in cultural heritage and tradition that, in the last years, has started to experience changes concerning gender norms. In 2022, a baseline survey was conducted in different schools from the Karnali and Madhesh Nepali provinces, as part of our project “Gender-sensitive Global Citizenship and Life Skills Education for Youth” funded by Reach Out to Asia (ROTA). Having collected lots of data about the teenagers’ gender attitudes as well as the gender norms in their households, we decided to conduct some additional analysis to get more insights on the data. In this article, we examine the differences in perceptions of gender equality between young girls and boys and between the provinces. Findings indicate that while boys exhibit generally more gender-equitable attitudes, girls are more aware of gender-related practices in households and related to gender-based violence, as well as striking differences in the two provinces.

Background: The Role of Family in Shaping Gender Attitudes

Humans learn social norms during childhood and adolescence primarily through their family. Among these social norms there are gender norms, which are all the practices and inherent beliefs surrounding gender roles. In the case of Nepal, the family –particularly fathers– are the decision-makers for marriage of their children, and there are strong social norms surrounding family honor in relationship to girl’s chastity [1]. These collective gender norms have been shown in literature to impact children and youth individual-level perceptions and behaviors on gender equality.

A previous study in the Lumbini province found that girls had lower sexual and reproductive health (SRH) knowledge, lower aspirations about marriage and education, and lower self-efficacy than boys. However, girls showed more equitable sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and gender attitudes than their male counterparts [2]. Additionally, Nepali women who report higher acceptance of traditional gender norms in their community are at a higher risk of both physical and sexual intimate partner violence [3]. In all, social gender norms impact girls and women more negatively than they impact men, and shape their experiences and their beliefs on how they should behave towards men in their community.

.

Our Study: How Household Gender Practices Affect Gender Attitudes Among Nepali Teens

The data collection for this study was conducted in the provinces of Karnali and Madhesh in Nepal, which offer contrasting socio-economic and geographical backgrounds and a rich context for analysis. Below is a description of the measures included in our survey:

.

Household Gender Practices: (1) Are your relatives allowed in the kitchen during menstruation?, (2) Do your relatives sleep somewhere else during menstruation?, (3) Did any of your family members get married below the age of 20?.

Gender Attitudes: (1) Gender Equitative Attitude Scale, (2) Gender-Equitative Management of the Household Budget, (3) Tolerance Towards Domestic Violence (DV), (4) Behavioral Intention Towards Own Domestic Violence, and (5) Awareness of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR).

.

These were our key findings:

1. What are the Traditional Gender Practices at Home?

- The majority of participants (74%) reported that, in their family, menstruating women are not allowed in the kitchen.

- About 37% of teens said that menstruating relatives sleep elsewhere during their periods.

- Approximately 43% had family members who married before the age of 20.

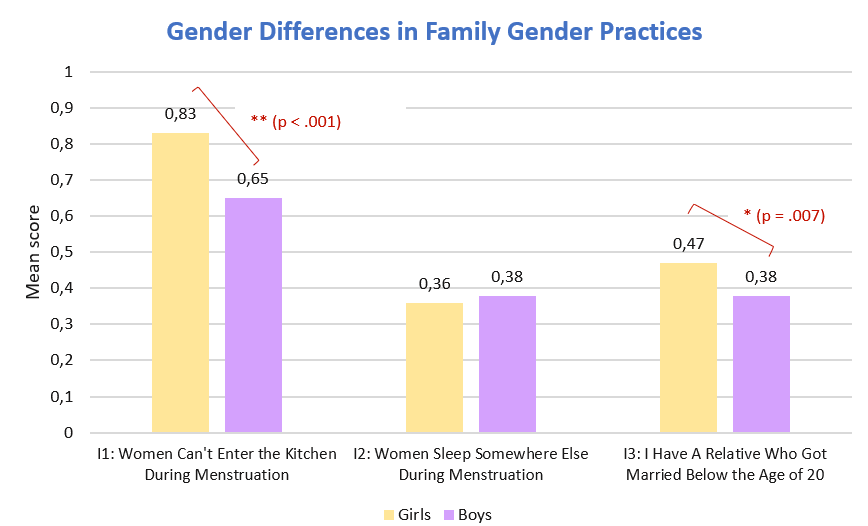

2. Girls are More Aware of Family Practices and More Traditional Than Boys

Teenage girls were more likely than boys to report traditional practices like kitchen restrictions during menstruation and early marriage of relatives

Note. The graph shows the mean scores in the three family gender practices among teenage girls and boys and the results of the T-Tests comparing the two genders. The scores range from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating no presence of traditional gender practice or a more equalitarian household and 1 indicating presence of the traditional gender practice or a more traditional household. Teenage girls were significantly more likely to report traditional family gender practices in I1 and I3 than boys were (p-value < 0.05).

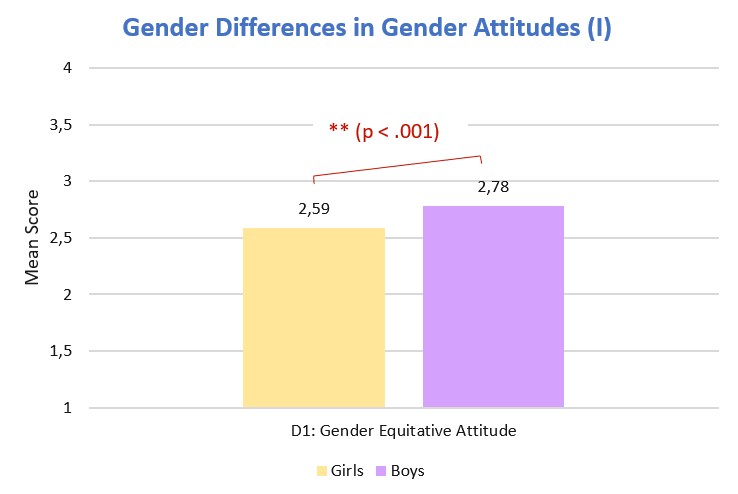

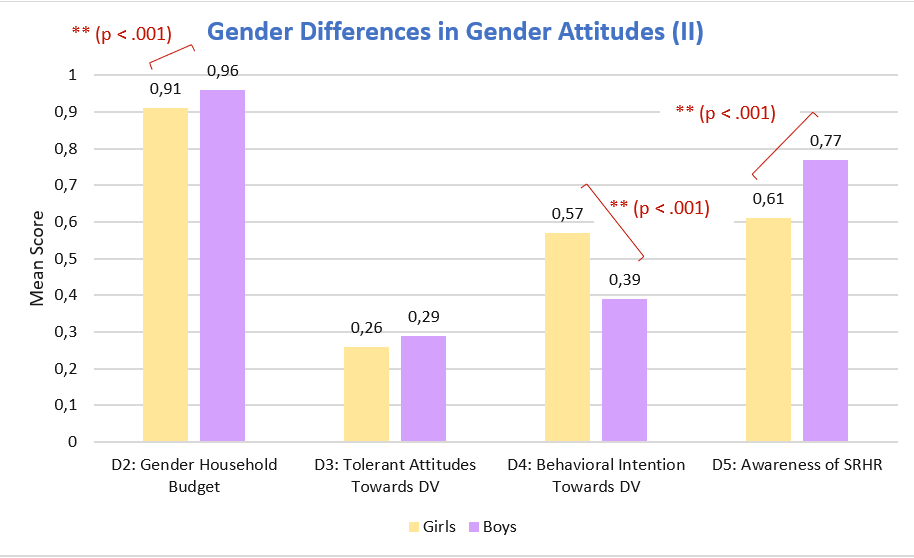

- Male participants exhibited more equitable gender attitudes and awareness of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) than females. However, girls were more likely than boys to say they would act assertively if experiencing domestic violence themselves.

Note. The graph shows the results of the T-Test comparing the mean score of D1: Gender Equitatable Attitude among teenage girls and boys. The score ranges from 1 to 4, with 1 indicating more traditional gender attitudes and 4 indicating more equitatable gender attitudes. Teenage boys were significantly more likely than girls to show equitable attitudes towards gender roles (p-value < 0.05).

Note. The graph shows the results of the T-Tests comparing the mean scores of the different gender attitude scales among teenage girls and boys. The scores range from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating more traditional gender attitudes and 1 indicating more equitative gender attitudes in D2, D4, and D5. In D3 0 indicates less tolerance towards DV or more equitative attitudes, and 1 indicates more tolerance towards DV or more traditional views. In D2 and D5, teenage boys were significantly more likely than girls to show equitative attitudes towards gender roles whereas in D4 teenage girls were more likely than boys to show equitative attitudes (p-value < 0.05).

3. Provincial Differences:

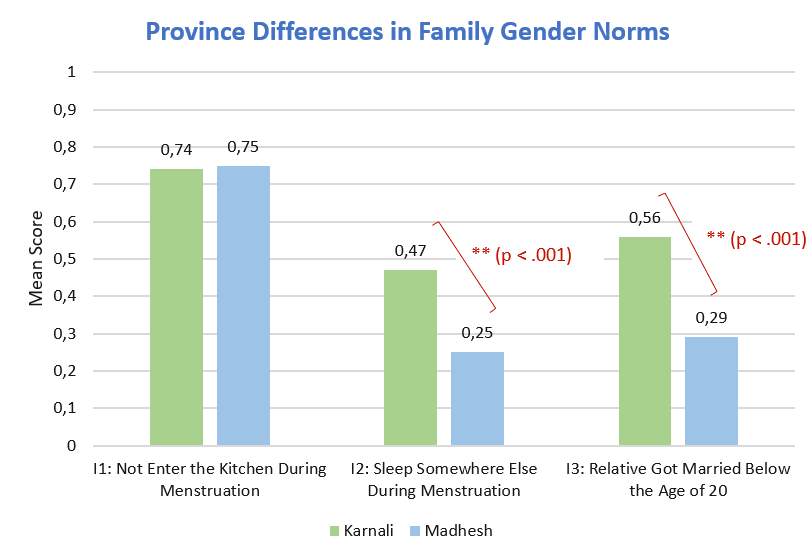

- Teens from Karnali province were more likely to report menstruation-related sleeping arrangements and early marriages than those from Madhesh province.

Note. The graph shows the mean scores in the three family gender practices among Karnali and Madhesh teenagers and the results of the T-Tests comparing the two provinces. The scores range from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating no presence of traditional gender practice or a more equalitarian household and 1 indicating presence of the traditional gender practice or a more traditional household. Teenagers in Karnali were significantly more likely to report traditional family gender practices in I1 and I3 than teenagers in Madhesh (p-value < 0.05).

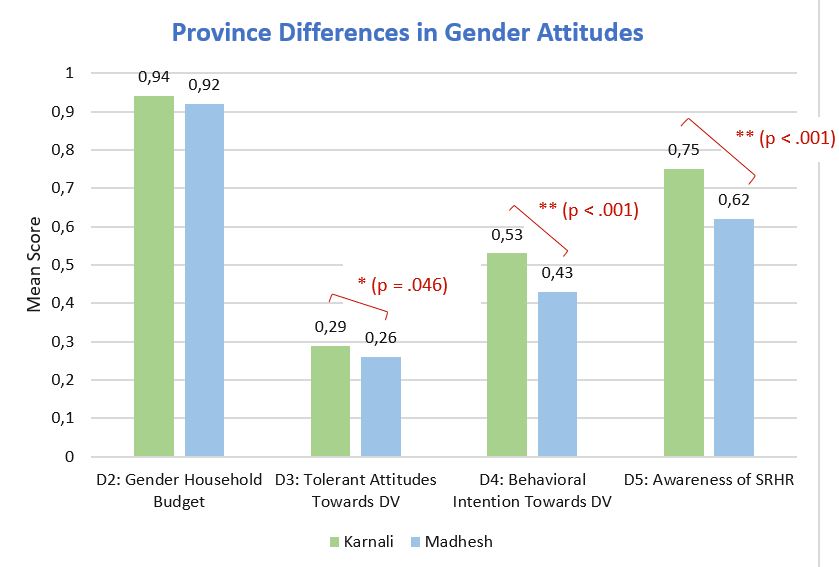

- Madhesh province participants were less likely to take concrete action against domestic violence (DV) and had less awareness of SRHR compared to their Karnali counterparts.

Note. The graph shows the results of the T-Tests comparing the mean scores of the different gender attitude scales among teenagers in Karnali and Madhesh. The scores range from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating more traditional gender attitudes and 1 indicating more equitative gender attitudes in D2, D4, and D5. In D3 0 indicates less tolerance towards DV or more equitative attitudes, and 1 indicates more tolerance towards DV or more traditional views. Teenagers from Karnali showed more equitative gender views in D4 and D5 than Madhesh teenagers, while at the same time showing more traditional gender attitudes in D3 than Madhesh participants (p-value < 0.05).

Impact of Household Gender Practices

How did the household gender practices affect beliefs of gender equality among teens? To assess this, we conducted regression analyses that revealed intriguing insights:

- Gender family practices were significantly associated with several indicators of gender attitudes in both directions: sometimes, more traditional households lead to more traditional beliefs and, in other instances, they were paired with more equitative beliefs.

- Young boys were more impacted than girls by their family gender practices, and teenagers from the Madhesh province were also more affected by their family gender practices than those from Karnali.

..

ConclusionThe findings of this secondary data analysis highlight significant gender disparities and cultural variances in the attitudes and experiences of teenagers in the Madhesh and Karnali provinces of Nepal. The pronounced gender divide in awareness and attitudes towards traditional gender practices underscores the vulnerability of teenage girls, who, despite their awareness, still hold traditional beliefs about gender equality. This suggests a critical need for targeted educational programs focusing on young girls to bridge this gap and foster a more equitable mindset.

.

Furthermore, the contrasting realities between Karnali province and Madhesh province teenagers reveal the complexity of gender dynamics across regions. While Karnali teenagers show more awareness and tolerance of traditional practices and domestic violence, Madhesh students exhibit a lower propensity for assertive responses towards own domestic violence and less SRHR awareness. These difference reflect the need for region-specific educational interventions to address the unique challenges and cultural contexts effectively.

.

Even if we could establish some connections between household gender practices and teenagers’ attitudes towards gender equality, the results were inconclusive and bidirectional. Thus, further research is required to fully understand these dynamics. Overall, Nepal’s journey towards gender equality is nuanced and multifaceted. As families and communities continue to evolve, so will the gender attitudes of its youth. This research offers a valuable glimpse into that evolving landscape, providing hope for a more equitable future.

.

References

- Morrow G, Yount KM, Bergenfeld I, Laterra A, Sadhvi K, Khan Z, Clark CJ. Adolescent boys’ and girls’ perspectives on social norms surrounding child marriage in Nepal. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2023;25(10):1277-1294.

- Yount KM, Durr RL, Bergenfeld I, Clark CJ, Khan Z, Laterra A, Pokhrel P, Sharma S. Community Gender Norms and Gender Gaps in Adolescent Agency in Nepal. Youth & Society. 2024;56(1):17-142.

- Clark CJ, Ferguson G, Shrestha B, Shrestha PN, Oakes JM, Gupta J, McGhee S, Cheong YF, Yount KM. Social norms and women’s risk of intimate partner violence in Nepal. Social Science & Medicine. 2018.