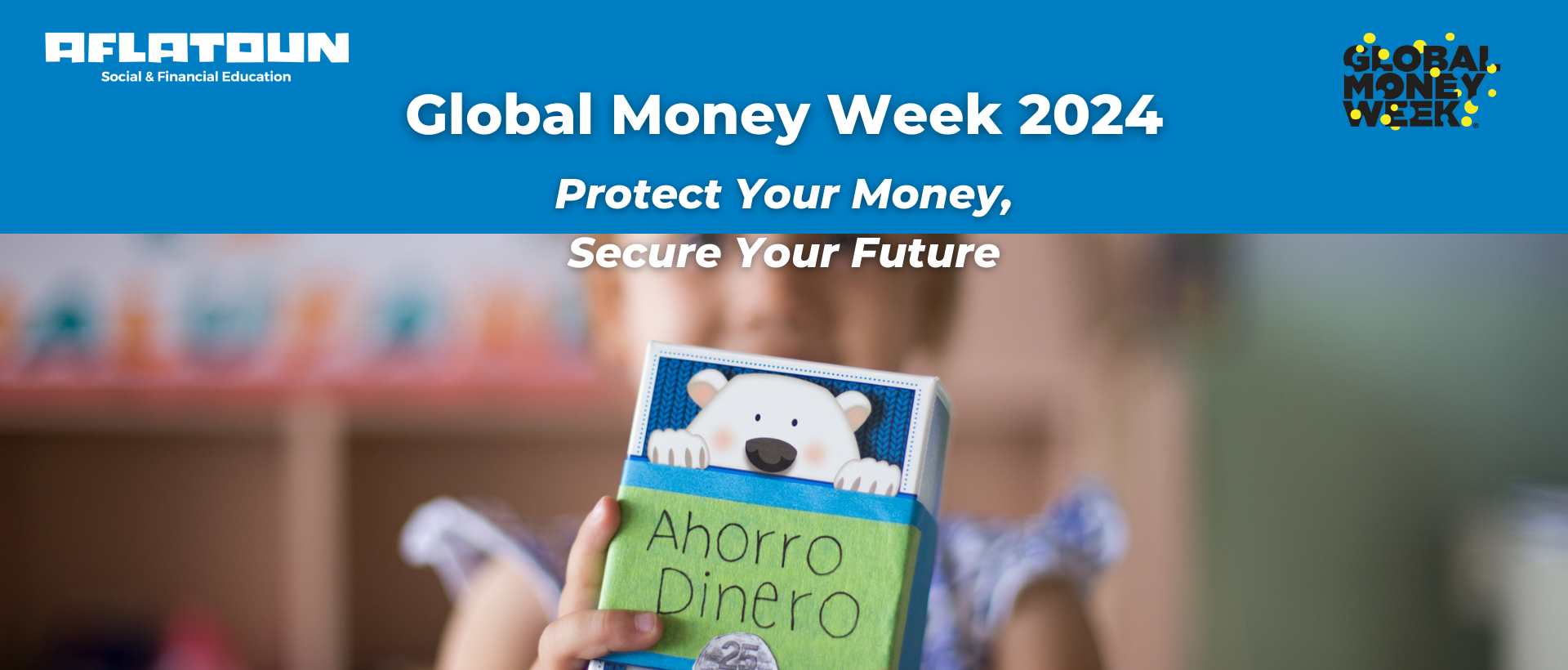

Anganwadis in Jodhpur’s Bilara district, the public childcare centres delivering prenatal and early childhood care, initiate delicate conversations around money matters so parents can plan confidently for their children’s needs. A financial literacy programme prepares young mothers to have a say when saving for their children’s future. Similar results are emerging across six countries, see Aflatoun’s story, “Empowering Parents, Securing Futures,” for the big picture:

*This article was prepared by Aflatoun International in collaboration with a local consultant, as part of a project funded by The Human Safety Net. All individual and village names mentioned in the article have been replaced with pseudonyms.

[Image: Group discussion at anganwadi]

Jaswant Sagar Dam on the Luni River in the western Rajasthan district of Jodhpur was built by the Marwar king Maharaja Jaswant Singh II in 1892. The Imperial Gazetteer of India noted that the dam fed one of the largest artificial lakes in the country, its overflow irrigating over twelve thousand acres in the southern part of the district for almost a century. After years of governmental neglect, the dam suffered multiple collapses between 1984 and ’86, creating a drought.

Rashid-ji, a retired engineer living in Ratalya village in the Bilara tehsil of Jodhpur, recounts that most of his neighbours opened bank accounts for the first time after this shock. ‘We used to have a good crop here. Now that we couldn’t depend on the dam for cropping moong (green gram), jowar (sorghum), jeera (cumin) and other spices, everyone started putting whatever they could in the bank.’ ‘

‘Where we live, opportunities to make a living have always been hard to come by,’ says the septuagenarian. ‘That is why our ancestors devised a system of keeping a rupee and a half aside from every five earned. Shareer mei peep aur jeb mei paisa, koi nahi rok sakta Marwari jaisa.’ (No one can stop the flow of pus from the body or money from the pocket like Marwaris.) The Marwar region, which includes Jodhpur and neighbouring districts in Rajasthan where this story has taken us, is popularly known for its thrifty culture, closely-knit trading communities, and sharp acumen for cash. It has historically played an outsized role in trade and finance in the Indian sub-continent.

[Image: Map of Rajasthan]

Do rupaye saugda. That is another popular Marwari colloquialism, translating to two rupees for every hundred loaned. That is the interest rate compounded monthly by local money lenders, or sahukaars, charging as high as 24% per annum on loans outside formal banking mechanisms. Suman, a new mother visiting Ratalya’s government-run childhood care centre, or anganwadi, explains the preference for such informal lenders despite their extortive rates. ‘He comes by the house for small sums, ₹2,000 or ₹5,000. I can request a few days’ extension if there is an issue with repaying on time.’ Banks impose penalties.

Goma Ram, a landless manual worker from a former Untouchable community, complains about the alienating experience at the bank. ‘You go there, and the manager will ask you for papers. Show your tax filings, proof of residence, and assets. Someone with a regular income can maintain a credit score. How can a daily wage earner or small shop owner produce such papers?’ The sahukaar is indifferent to papers.

Farm incomes help in tough times

[Image: Kanna Ram stands outside his house]

Kanna Ram, 58, and his wife are daily wage earners who work on farms, construction sites, warehouses, or wherever a hand is needed. They live in Ratalya with their daughter-in-law, who recently gave birth to a grandson. A cloth swing in the courtyard in the middle of Kanna’s home swaddles the three-month-old infant napping in the afternoon sun as he sits on a low khatiya bed made of woven rope and shares his plans for his first grandson, reflecting how many in the village think about financial planning before attending the financial literacy programme.

Like many others in the village, Kanna’s son has migrated in search of work, moving to the tech hub of Bengaluru twelve hundred miles south. Migration has become a way of life for young men in Ratalya, working in the construction sector in the cities or agro-industries and small businesses in nearby towns. Remittances form a mainstay of the rural economy.

‘We have never been to a seth-sahukaar. It’s better to cut costs than mortgage your land,’ says Kanna. What if there is an emergency? ‘We only take loans within the family. When my bahu (daughter-in-law) came to this house after marriage, all I loaned for the wedding was around thirty thousand rupees. Only from relatives. Cutting costs is better than making a big show on credit.’

Weddings are often a source of considerable mental turmoil and financial strain, as conspicuous expenditure on food, clothes, jewellery and entertainment at weddings is equated with a family’s social status and prestige. The Bollywood-style wedding is ruining families, the latest national-level data on credit behaviour shows, with marriage-related loans topping the charts among causes for farmer indebtedness. Against common perception, banks are responsible for more stressed small-ticket loans than informal money lenders.

Putting a child through higher education in private institutes is another significant dip into savings and credit. ‘We tend to go towards manual labour in our family,’ Kanna explains, adding, ‘Having a degree is no guarantee for a job. It is better to learn a trade or pick up a skill. The important thing is for children to follow their interests. That’s the only way to become skilled at anything.’

A technical or vocational course at an ordinary rural college today costs ₹32,137 per year, six times that of an undergraduate degree, latest government figures indicate. Kanna wants to see his grandson train at an industrial technical institute (ITI) to become a mechanic, which he or his son could not. He has to start saving towards this from an early stage.

‘We try to save rather than take loans,’ says Kanna. Several days a year, he and his wife work on projects allocated by the panchayat, a local governance body that oversees public works under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS). This influential programme assures poor and marginalised rural families 100 days of guaranteed work. The digitalisation of NREGS payments has also ensured that everyone in the family has a bank account.

‘People know where to come whenever there is work in the village. We meet our regular expenses from what my wife and I make as labourers. It’s hard to save anything every month.’ Daily wages in this region are relatively high—at ₹350 – 400 (3.99 – 4.56 USD) for a day’s work, earnings here are above the national rural average, which stood at ₹186.50 (2.12 USD) for unskilled and ₹264.70 (3.02 USD) for skilled male workers in 2022-23.

In the last crop cycle, Kanna Ram’s family earned around one hun fifty thousand rupees from growing legumes like moong and chana, millets and spices. They will set aside money for the next cycle from this sum. Seeds, pesticides, hired hands in the cutting season, transportation, etc., rack up a tidy bill even with the whole family working on the farm. Farm incomes during cultivation season, usually with one harvest a year, make up the bulk of savings or go towards more significant expenses. This means saving is usually a once-in-a-year affair, depending on the rain.

Savings happen before spending

‘The anganwadi has been very good to us. Rami [Devi, a childcare worker] is my neighbour, and she visits whenever it is time for a vaccination shot.’ Kanna Ram wants to send his daughter-in-law to the centre again in a few months now that the newborn is healthy.

Rami Devi taught Hindi in a private school before being appointed an anganwadi worker in her village. She goes door to door to survey households, map infants’ and mothers’ needs, and ensure government services reach them.

Ratalya’s anganwadi, which covers 468 households and a population of around 1,700, has implemented financial literacy modules under the Right Start programme for the better part of a year. This overlooked node in the public prenatal and early childhood care system has been completely transformed.

‘Before they started attending sessions at the anganwadi, the women here used to think that savings were what was left at the end of the month,’ says Rami, recounting the initial challenges in implementing the programme. ‘The financial literacy programme encourages them to track their income and expenditure, plan in advance and set achievable savings targets for their child’s needs. This way, we tried to show them that savings have to be accounted for before beginning to spend.’

[Image: The anganwadi at Ratalya was identified under Save the Children, India’s ‘The Right Start’ programme]

‘There is no security in business or farming anymore. It is best to prepare kids for stable jobs with an assured income,’ believes Rukma Devi, a grandmother who has come to the centre with her daughter-in-law Pushpa. At the first financial literacy session, guardians are told to list their expenses and identify targets for their children.

[Image: Rami Devi is in charge of Ratalya’s anganwadi]

‘I want my girl to learn English. I am now trying to admit her to the Hindi medium school in Bilara. Still, she should study in English after third grade,’ says Kavita, 25, a regular at the Right Start sessions in the anganwadi and mother of four-year-old Meena. With the rising preference for private schools, even pre-primary tuition costs parents at least ₹2,000 (22.87 USD) a year, leaving aside other expenses on uniforms, books and transport. An English medium school will charge at least ₹7,000 (80.04 USD) annually.

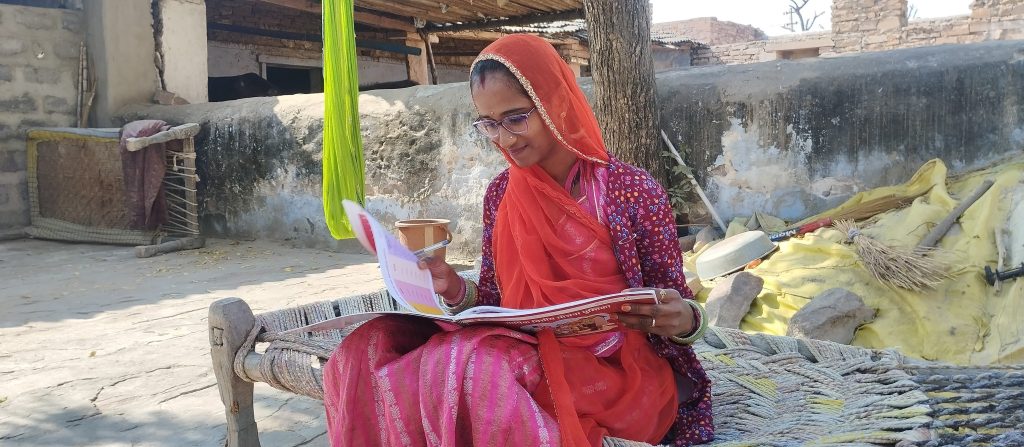

Kavita moved to Ratalya after marriage. ‘I had to discontinue my studies when I was ten because of financial constraints at home, so I started helping an uncle who ran a call centre. I learned data entry on the laptop and worked as a call operator from home for some months after moving here. I learned the value of saving only after I started working.’

Kavita had wanted to become a doctor. She wants her girl to be able to choose. Higher studies, she estimates, will easily involve a cost of four to five lakhs (around 4,574 – 5,718 USD). She and her husband may consider an education loan if their savings fall short.

[Image: Kavita maintains a diary to track regular savings]

After feeding the animals awaiting her return, Kavita washes up and produces an expense-tracker journal that she has been maintaining. It has coloured columns that record dates, incomes, expenses, and savings. ‘This diary is something I have taken to after attending the [Right Start] sessions at the anganwadi,’ Kavita says. She uses it to help her husband keep accounts for a ‘fancy goods’ store in Bilara town where he sells toys, cards, imitative jewellery, cosmetics and various household items. Her family also owns 25 bigha, or around 4,125 square feet of land, some of which has been leased out. The crops are rainfed, and the whole family is involved in the harvesting, which is done by hand. Last year, they put aside around ₹60,000 (685.99 USD) after the harvest. Kavita has set a monthly savings target of ₹6,000 (68.62 USD). Managing the accounts makes her feel productive since women are often told to avoid working outside the home after marriage.

‘Men can earn, women have to save’

Kavita emphasises this when asked about the value of financial literacy to her. Brides are often left in the care of their in-laws when their young husbands work outside the district. ‘They sometimes make excuses to avoid our meetings or start talking on the phone. Most have not studied beyond the fifth grade but know basic arithmetic. Our elders were more involved in managing household budgets when money was scarce. Women keep away from these matters today.’

‘My in-laws were supportive of me getting a job. The company I was working in shifted to Jodhpur, so I quit… I think a girl should have a job and know how to manage expenses before she gets married.’ When the question arises of what would be considered the ideal age to get children married, the women surrounding Kavita share a laugh when she says, ‘Not a day before 25.’

Most women who come to the anganwadi in Ratalya have responsibilities at the farm and rear animals aside from managing their homes. Around 80 percent of farm work in India, including sowing, winnowing, harvesting and other non-mechanized farm occupations, is undertaken by women. Kavita complains that the value of their work is not usually recognised, even by the women themselves.

In November 2016, the Government of India scrapped all ₹500 and ₹1,000 denomination notes in circulation. This forced people to queue up to deposit their petty cash but came as a shot in the arm for the formal banking system. ‘Earlier, she would keep the cash in a jar of dal (legumes), sometimes under a mattress,’ said Payal, laughing at her friend Vidya in the anganwadi. Like Kavita, many parents now have fixed deposits at the bank for their children. The Rajasthan government’s Sukanya Samriddhi Yojana (Girl Child Prosperity Scheme) has promoted 100 per cent inclusion in banking for all girls who come to Ratalya’s anganwadi and encourages saving. It is a government-backed fixed savings scheme that matures when girls turn 21. Many women use the Sukanya Samriddhi bank account to save for their daughters after attending the Right Start financial literacy programme.

‘In the second session I attended last October, they taught us to differentiate between wants and needs,’ Kavita narrates. When speaking to parents in Ratalya, alcohol tops the list of wants, or unnecessary expenses, for men, while women agree that excessive spending on gold and clothes can be a want. Dahej, or dowry, parents agree, is also an unnecessary expense.

On the other hand, building a pakka makaan, or a permanent dwelling, is now considered a necessity. Brick-and-mortar constructions were not the norm here, even for the previous generation. Some parents at the anganwadi agree that they might consider taking a home loan from the local cooperative bank. In previous sessions, they discussed the problems of taking loans from family members. ‘It is a matter of your name. Small squabbles over not repaying relatives can sour close relations,’ says Kavita.

‘Small things, like sending my niece to the grocer’s or involving her in deciding whether she needs that trinket she’s been stubborn about—these go towards making kids comfortable with handling money.’ She adds that children should also be involved in making financial decisions at home after they turn 15 or 16 so that they can handle these matters confidently when running a household themselves.